by Mike Mackey

On December 7, 1941, the Empire of Japan attacked United States military installations in the Hawaiian Islands. This action brought the United States into World War II. One result of that attack was the forced relocation of Japanese and Japanese Americans from their homes on the West Coast of the United States. More than 14,000 of those people would pass through the gates of the Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Wyoming.

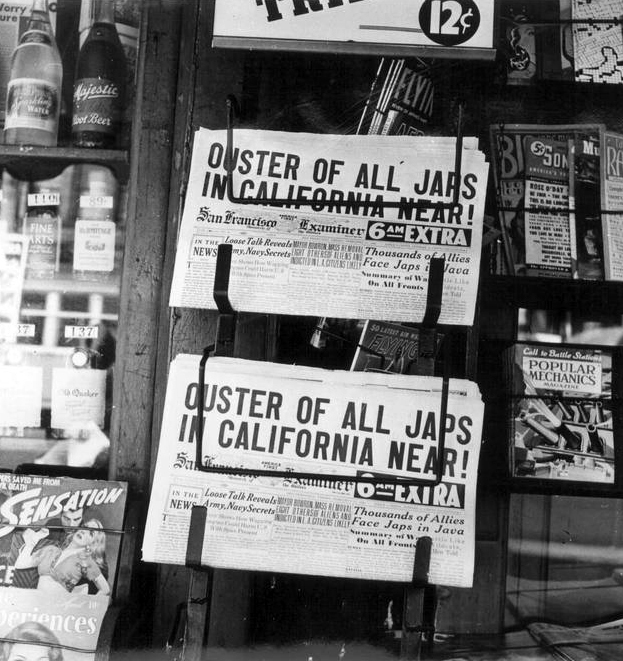

Anti-Japanese headlines hit the streets (WRA #9066P38)

Some federal government and U. S. military leaders claimed that the forced relocation of people of Japanese ancestry was a "military necessity." As later investigations revealed, this was not the case. The bombing of Pearl Harbor became the excuse used to rid the West Coast of its Japanese residents; however, the real reason for their removal was rooted in anti-Japanese sentiment that existed in California for forty years before the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The anti-Japanese movement in California was actually part of a larger anti-Asian feeling that began in 1850 with the arrival of Chinese immigrants. The Chinese, like others flocking to California at that time, were searching for gold. New racially motivated laws that focused on the Chinese were quickly established. The Chinese were forced to pay a "foreign miners tax" before they could search for gold and they were added to a list of those who could not testify against white people in a court of law, joining Blacks and Native Americans.

As the gold fever slowly died in California, the Chinese began to work as laborers for a number of railroad companies throughout the American West. They also found jobs in the agricultural sector. The Chinese were often willing to work for half the money paid to white workers performing the same job. This resulted in pressure by politicians and labor organizations on the federal government for control of the Chinese population in the United States. These groups saw the Chinese as a threat to the American way of life. As a result, President Chester Arthur signed the Chinese Exclusion Act into law in 1882. This law barred the immigration of Chinese laborers to the United States.

Notice to Japanese-ancestry citizens regarding relocation (WRA #9066P35)

The Exclusion Act resulted in a decline in the Chinese population in the Unites States, particularly in California. This population decline led to a labor shortage in that state's agricultural industry. Shortly after the Chinese started leaving in the 1880s, Japanese laborers began arriving on the West Coast from Hawaii where they had been working in the sugar cane fields since the 1860s.

The Japanese were initially welcomed as they relieved the existing labor shortage. However, unlike the Chinese, the Japanese were not content with merely working for others. They had a deep desire to own their own farms and work for themselves. In a short period of time, the Japanese were also seen as a threat.

By 1905 an anti-Japanese movement in California became active and remained so until after the conclusion of World War II in 1945. The Japanese, however, could not be dealt within the same manner as the Chinese. Japan was a growing economic and military power important to the United States. To appease anti-Japanese politicians in California, President Theodore Roosevelt reached an understanding with the Japanese government. This understanding, termed the "Gentlemen's Agreement," halted the immigration of laborers from Japan. The agreement did not stop the immigration of all Japanese people.

Brides of Japanese laborers, already on the West Coast before the conclusion of the Gentlemen's Agreement, began arriving in California, causing the residents of that state to feel betrayed by the federal government. As a result, the state legislature passed the California Alien Land Law in 1913. This law prohibited "aliens ineligible to citizenship" from owning land. The term "aliens ineligible to citizenship" was the key to anti-Japanese legislation. The original naturalization laws of the United States, dating to the 1790s, only allowed for "free white persons" to become citizens. This was changed to include people of African descent following the Civil War. Thus, the "Issei," or first generation Japanese immigrants, could not become American citizens.

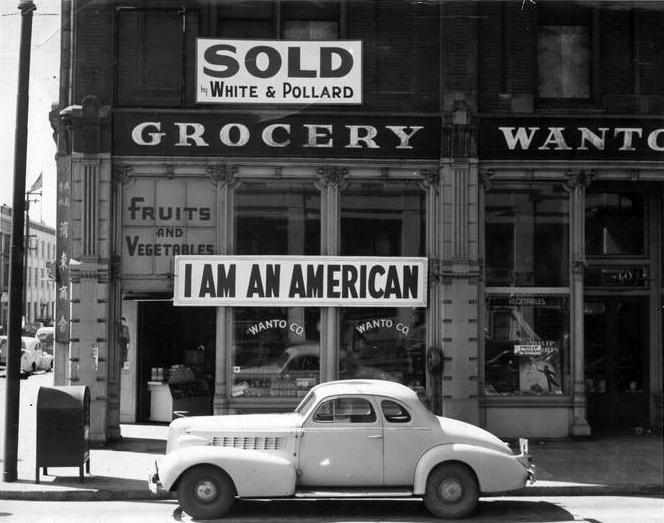

Japanese-American sentiments (WRA #9066P51)

As the brides of Japanese laborers began to arrive and bear children, the Issei purchased land in California in the names of their American-born offspring. The "Nisei," or second generation, were citizens by birth. In 1920, one of California's United States Senators, James D. Phelan, ran his election campaign on the slogan, "Keep California White." Though Phelan lost the election, the state legislature passed a newer version of the California Alien Land Law. The Japanese also easily circumvented the 1920 version.

Through the early 1920s there was a national outcry for immigration control. As a result, the federal government passed the Immigration Act of 1924. This law set quotas by country for immigration into the United States. However, there would be no quota for countries whose people were "ineligible to citizenship," which included the Japanese. Immigration from Japan had been halted, but there was still the problem of how to get rid of the Japanese already living on the West Coast.

By 1940 there were 112,000 people of Japanese ancestry living on the West Coast. Nearly 94,000 of them resided in California. The bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941 facilitated the removal of the vast majority of these people from California and the West Coast. Following that attack, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) rounded up a number of Japanese, German and Italian aliens whom it considered a possible threat to national security. On the West Coast, General John DeWitt was picked to head the newly formed Western Defense Command.

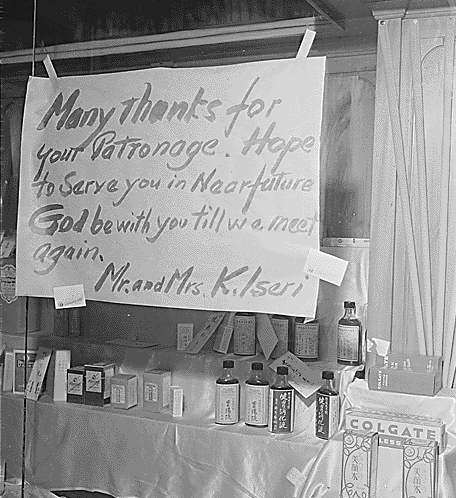

Farewell Message (WRA #9066P46)

DeWitt had seen accusations of unpreparedness leveled against his fellow commanders in Hawaii, and some of those officers were dismissed. He was determined that the area under his command would not be attacked from outside the country, or from within. DeWitt originally proposed to round up all German, Italian and Japanese aliens over the age of thirteen and relocate them to the interior of the country. He had initially opposed the removal of any American citizens. However, DeWitt's preoccupation with thoughts of possible invasion and sabotage by a Japanese fifth-column left him open to other influences, both military and civilian.

General Allen W. Gullion, the army's Provost Marshall General, saw the possibility of sabotage at every turn. After extensive lobbying for the removal of the Japanese by the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, Gullion sent one of his underlings, Karl Bendetsen, for a first hand view of the situation. Influence from Bendetsen, sensationalized newspaper stories, and racially oriented special interest groups in California caused DeWitt to rethink his situation.

West Coast politicians were also influential. California Attorney General Earl Warren reasoned that since no act of sabotage had been undertaken by any individual of Japanese ancestry following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, it only meant that Japanese people were biding their time and would attack when least expected. (1)

Train Station (Ethel Ryan Collection #82.01.83.P)

Special interest groups in California coerced DeWitt. Despite comments by General Mark Clark, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, and United States Attorney General Francis Biddle to the effect that the removal of the Japanese from the West Coast was unnecessary, DeWitt was swayed by other influences. Fear of the West Coast Japanese soon spread from California to Washington D. C. As a result, on February 19, 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. This order allowed civilian and military authorities to designate restricted zones and determine what people, if any, should be removed from those zones. Though the order mentioned no specific race or ethnic group, it came to focus on people of Japanese descent. As a result, nearly 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry, two thirds of who were American citizens, were forcibly removed from the West Coast.

On March 2, 1942, General DeWitt divided the West Coast states of Washington, Oregon and California, as well as the state of Arizona, into two specific "military areas." These areas were split further into "prohibited" and "restricted" zones. In these zones, which ran the length of the West Coast shoreline, a curfew was established, but it applied only to enemy aliens and people of Japanese descent. These military areas were further divided into 107 districts. Each district contained approximately one thousand people of Japanese ancestry. The smaller districts would eventually facilitate the roundup of the Japanese.

Relocation Camp looking east by southeast from Reservoir Hill, Photographer: Tom Parker, September 16, 1942 (Ethel Ryan Collection #82.01.22.P)

In late March and early April of 1942, the roundups began. Notices were posted in each district. All people of Japanese ancestry were given a week to ten days to conclude any business, lock up their homes and report to a designated location on a specified date with no more baggage than they could carry. As a result of this order, the "evacuees," as the government described them, usually sold what they could not take with them.

Automobiles were sold for less than half their worth; other belongings often went for ten cents on the dollar; pets were given away or left behind. Those who stored belongings often discovered, after the war, that those items had been stolen or vandalized.

On the specified day, evacuees appeared with their baggage, not knowing where they were going or what would become of them, as their destinations were kept secret.

The evacuees were loaded onto trains and buses destined for what the army described as "assembly centers." The assembly centers were established along the entire length of America's Pacific Coast, with the greatest number located in California.

A family's living area in barracks (Ethel Ryan Collection #82.01.92.P)

In most instances, the assembly centers were established at fairgrounds or horse racing tracks. These facilities had water and some housing. The housing took the form of exhibit buildings and horse stalls. The horse stalls were whitewashed, as the inmates reported, usually right over the manure, which was splattered, on the walls. Where housing was not available, the evacuees lived in tents or jerry-built barracks.

While the Japanese were held in the assembly centers, larger camps under the control of the newly established War Relocation Authority (WRA), a civilian run organization, were being constructed farther inland. Two of these camps, known as "relocation centers," were to be built in each of the states of California, Arizona and Arkansas, with one each being located in Idaho, Utah, Colorado and Wyoming. The camp in Wyoming, known as the Heart Mountain Relocation Center, was to be constructed on land that was part of a federal reclamation project located in the northwest corner of the state, halfway between the communities of Powell and Cody.

Prior to the construction of the Heart Mountain Relocation Center, Joseph C. O'Mahoney, Wyoming senior U. S. Senator, had contacted prominent individuals in the Powell/Cody area and asked for their reaction to the possible construction of such a facility. Powell Mayor Ora Bever opposed the proposed camp while Cody Mayor Paul Stock said he did not object to the camp but did not want the Japanese allowed into his town (2). Wyoming Governor Nels Smith made his views perfectly clear when he informed Milton Eisenhower, whom then headed the WRA, that if the Japanese were brought into Wyoming "they would be hanging from every tree." (3) In spite of these comments, the majority of residents in the Powell/Cody area had no opposition to the camp. They saw it as a potential relief to the poor economic situation, which had existed in the area for the preceding fifteen years. (4)

A Camp Government Meeting (Ethel Ryan Collection #82.01.75.P)

There were several reasons for choosing the site between Powell and Cody. Since the center had to house at least 10,000 people, it would need a dependable water supply and an economical form of transportation to keep the facility supplied with food and other necessities. Isolation from local population centers was also a factor in choosing a campsite. The land of the Heart Mountain Reclamation Project met all of those requirements. The Shoshone River was nearby and would be a reliable source of water. The Vocation railroad siding below the campsite guaranteed cheap transportation and the location, twelve miles from Powell and thirteen miles from Cody, meant that camp residents would be isolated from the local populations.

By early June of 1942, construction of the Heart Mountain Relocation Center was underway. Within a matter of weeks nearly 2,000 laborers were at the site. The economic hard times in Powell and Cody changed overnight. Government contractors hired anyone who could swing a hammer. Housing for the future inmates consisted of a series of barrack buildings. Each building was 120 feet long and twenty feet wide.

Heart Mountain Hospital (Ethel Ryan Collection #82.01.51.P)

The barrack, which could be constructed in only fifty-five minutes if all the materials were available, was divided into six apartments. The size of the single room apartments varied from 20 x 16 to 20 x 20 to 20 x 24 foot rooms. The larger apartments were for families of up to six members. Furnishings for the apartments consisted of one pot-bellied stove for heat, one light fixture hanging from the ceiling in the center of the room, and an army cot with two blankets for each occupant.

In each block of barrack, a mess hall, latrine and showers, and a laundry area were constructed. The contractors also built a hospital (a string of barracks tied together with a long hallway at one end) and administration buildings. Additional barracks were used for the school and as housing for military personnel who would guard the inmates. When construction was completed, each building was then covered with tarpaper. In approximately sixty days, the construction was, for the most part, completed. There were still some buildings to finish and stoves to install, and insulation (in the form of celotex) did not arrive until December of 1942. However, by the second week of August 1942, the Heart Mountain Relocation Center's first Director, C. E. Rachford, announced that the camp was ready for occupation.

Elementary School Classroom (Ethel Ryan Collection #82.01.59.P)

The first trainload of internees arrived at Heart Mountain on August 11, 1942. The editor of the Powell Tribune said that the camp had been constructed at a "most attractive site" in a "beautiful" area (5). The internee's first impressions were markedly different. Ben Okura, one of the first to arrive, said the place was "pretty spooky." The first impressions of Heart Mountain from other internees fell somewhere into the following description: "barren, desolate, flat open desert, bleak, scrubby, lonely, dusty and a plain of sagebrush with not a tree in sight." (6) Many of the women sat down and cried when they saw what was to be their new home.

As with the scenery at Heart Mountain, internees were not impressed with their apartments. Contractors used green lumber during construction. In time, as the wood dried, it shrank and left spaces between the boards from a quarter inch to a half-inch wide. The tar paper did not keep the dirt out. Windows were installed crooked and often would not open or close tightly. Many internees, with tools ordered from the Sears & Roebuck catalogue, made their own repairs. Open ceilings in each apartment restricted privacy until celotex was installed late in the year.

Home Economics Class (Ethel Ryan Collection #82.01.45.P)

The food served at Heart Mountain was described as fair to poor and there was never enough during the early months after the camp opened. Stewards working for the administration said the problems centered on a handful of people who complained no matter how good the food was. Internees said the problem was in the administration, where stewards, who had no experience feeding such large groups of people, were more concerned that cooks fill out requisition forms correctly. Following an investigation by nine Caucasian teachers working at the camp, the head steward was replaced and the situation in the mess halls improved considerably.

One month after the Heart Mountain Relocation Center opened, the population reached 6,281. By the end of the first week of October 1942, more than 10,000 people were living at the camp. Once the food and housing situations were straightened out, internees moved to establish some semblance of a "normal" life. Adults had to find jobs to pay for clothes and the everyday necessities of life that the government did not supply, and the children had to be educated. There were also concerns about camp government and the establishment of a newspaper at Heart Mountain.

Tosh Asano, run out of bounds in sub-zero weather, Photographer: Hikaru Iwasaki, November 25, 1943 (Ethel Ryan Collection #82.01.04.P)

Bill Hosokawa tackled the problem of establishing a camp newspaper. With a degree in journalism and several years experience as a foreign correspondent in Southeast Asia and China, Hosokawa became the founding editor of the Heart Mountain Sentinel. He felt that a newspaper would give people in the camp a sense of community. It was important to let the more than 10,000 residents know what was going on both inside the barbed wire enclosure and in the outside world. With a circulation of 6,000, the first edition of the Sentinel appeared on October 24, 1942, and was distributed every Saturday until the summer of 1945, shortly before the camp closed.

A camp government was also established, but the process took time. This government consisted of Block Chairmen and Block Managers. The chairman was to represent the internees and present their complaints to the administration while the manager was to see that administration policy was carried out. Historian Douglas Nelson said that community government at Heart Mountain was a farce.

Young girls enjoy a summer day at the pool (Ethel Ryan Collection #82.01.71.P)

Bill Hosokawa agreed, asking, "Have you ever heard of democratic self government behind the barbed wire of a prison camp?" (7) In spite of their lack of power, the administration felt that those serving in camp government were instrumental in helping to solve problems and avoid labor strikes.

The WRA decided early on that the relocation centers were to be self sufficient, with all the work being done by the internees. It was also decided that the internees could not be paid more than a private in the army. While army privates were being paid $21 per month, professional people of Japanese ancestry working at Heart Mountain were paid $19 per month.

Doctor Ito, in charge of pediatrics at the Heart Mountain Hospital, was paid $228 per year at the same time that Caucasian nurses working at the hospital were paid $1,800 per year.

Another example of the disparity in pay can be seen in the camp's education program. Internee teachers were paid $228 per year with base salaries for Caucasian instructors set at $2,000 per year; senior teachers were paid $2,600 annually.

Young boy of Japanese ancestry from California learns to ice skate, Photographer: Tom Parker, January 10, 1943 (Ethel Ryan Collection #82.01.13.P)

This low pay scale, along with boredom and confinement to the camp, was incentive for some at Heart Mountain to look outside for employment. As the internees began arriving at Heart Mountain in the autumn of 1942, many local laborers had already left the area for the service or in search of higher.Paying war industry jobs outside of Wyoming. As time for the fall harvest of beans and sugar beets approached, Wyoming and other western states were suffering from a severe labor shortage. Many internees volunteered to work for area farmers, but the WRA required that they be paid the prevailing wage. Farmers quickly agreed to this stipulation, but Wyoming Governor Nels Smith did not. The governor had no problem with the pay scale, but he wanted the State of Wyoming to have control of the workers. The WRA refused and the internees stayed in the camp. While the crops sat in the fields, irate farmers bombarded Smith's office with letters describing the impending economic disaster that would take place when their crops rotted. At the last minute Smith relented, and internees, under the control of the WRA, harvested the crops of the grateful farmers.

On August 6, 1942, the WRA hired C. D. Carter as Superintendent of Education at Heart Mountain, and John Corbett as high school principal. These two men were presented with the daunting task of establishing a school system at the camp that could be accredited by the Wyoming State Board of Education. Carter and Corbett began hiring teachers and developing a curriculum almost immediately. Instructors had to qualify for a Wyoming teaching certificate. The teaching certificates for the few internees who taught were stamped on the back, "Valid at Heart Mountain Only." With the new teachers working together to develop the curriculum, school administrators did their best to procure supplies.

Heart Mountain Boy Scout (Ethel Ryan Collection #82.01.74.P)

The schools opened on October 5, 1942, in temporary quarters. A block of barracks was set aside for use as classrooms. Books did not arrive until December and then only in limited numbers. If a student had homework, he or she had to check out the textbook for the evening. Paper and pencils were also in short supply. The chalkboard was a piece of plywood painted black.

Students sat on benches, and though some teachers had a table, others used boxes for desks. Students who sat in the front of the classroom near the potbellied stoves roasted, while those who sat in the back wore coats to keep from freezing. The open ceilings made for continuous distractions as the noise from one classroom invaded adjacent rooms. A Wyoming high school accreditation committee visiting Heart Mountain in 1942 "did not feel that the physical facilities were on a par with other schools of the State." (8) The Wyoming State Board of Education did not assign a rating to the Heart Mountain schools that year.

In 1943, as supplies and more textbooks began to arrive, the elementary school was reorganized and construction began on a new high school.

The new high school, completed on May 27, 1943, had regular classrooms, a library, a large home economics room, machine shop, wood shop and a combination auditorium/gymnasium which seated 700 for basketball games and 1,100 for stage productions. During the 1943-44 school year, the Heart Mountain High School began participating in interscholastic athletics.

Football was a popular high school sport and all games were played at the camp.

Internees look on as water is turned into the canal, Photographer: Chas E. Mace, June 5, 1943 (Ethel Ryan Collection #82.01.35.P)

The Heart Mountain Eagles suffered only one defeat in football in two years. That 19-13 loss came at the hands of the Casper Mustangs. Casper's all-state fullback, 210.Pound Leroy Pearce (the center for the Eagles weighed in at 130 pounds), scored two touchdowns in that game. Basketball was the most popular high school sport and allowed for the closest contact between Heart Mountain students and students from the outside.

Unlike the football team, the boys basketball team was allowed to travel to schools outside the camp, as were the girls' basketball and volleyball teams. The basketball team was quick, but usually gave away a distinct height advantage. The competition was fierce, however, and enjoyed by participant and spectator alike.

The very young and the older residents of Heart Mountain who could not work or attend school faced the biggest problem in camp--boredom. The camp activity director tried to keep the internees occupied. There were two movie theaters in camp, the Dawn and the Pagoda. The price for attending a movie was a nickel for children and a dime for adults. During the time the camp was open, the movies took in more than $48,000. During the summer months, softball and baseball were the most popular activities.

Eiichi Sakauye, agricultural statistician, holds the first harvested watermelon, Photographer Bud Aoyama, September 1943 (Ethel Ryan Collection #82.01.42.P)

In 1943, a giant pit was dug near the irrigation canal that ran through the camp. The pit became the camp swimming pool and was a favorite gathering place for the younger crowd. Adult activities consisted of sewing, knitting, woodcarving and flower arranging. Traditional Japanese activities like Kabuki theater and Bon Odori (the annual festival for the dead) were popular but discouraged by camp administrators who insisted on previewing such activities before permitting them to proceed.

During the winter months, judo, boxing, basketball, volleyball, badminton and weight lifting were all popular indoor activities. More traditional Japanese activities held indoors consisted of bonsai classes, games of goh and shogi, calligraphy and haiku. The most popular outdoor winter activity was ice-skating.

The majority of Heart Mountain's residents had never seen an ice skate prior to coming to Wyoming. But cold weather and a great deal of free time resulted in many internees becoming excellent skaters. The Sears & Roebuck and Montgomery Ward mail order companies made a great deal of money selling ice skates at Heart Mountain.

One of the most popular activities for both boys and girls was scouting. The boys, belonging to Troop 379, 145, or 345, swam, hiked, and camped on the banks of the Shoshone River below the relocation center. The girls also camped and hiked around Heart Mountain and were lucky enough to make a trip to Cody and tour the Buffalo Bill Museum. For the boys there was the Boys Scouts Drum and Bugle Corps and the girls had a drill team. The two got together every year on the Fourth of July and paraded between the barracks. There were also meetings and jamborees with scouts from nearby Powell and Cody. With activities usually confined to the area around camp, the social workers at Heart Mountain felt that restrictive life in the center was having an adverse affect on the children.

Second Lieutenant Moe Yonemura conversing with draftees, Photographer: Hikaru Iwasaki, March 20, 1944 (Ethel Ryan Collection #82.01.16.P)

The administration arranged for the 500 scouts in the camp, male and female, to spend one week camping and hiking in Yellowstone National Park. This plan was carried out with the scouts going to the Park in groups of 100 during the summer of 1944.

Attending church was another important activity. The camp had a Catholic Church and a Community Christian Church. The latter usually held joint services attended by the Methodists, Baptists, Salvation Army, Reform Christians and Seventh Day Adventists. Two thirds of those who attended church at Heart Mountain were Buddhists. The administration forced the Buddhists to attend the same church even though some Buddhist priests wanted to start separate churches of their own. Since the constitutional rights of internees had already been violated through their forced removal from the West Coast, administrators had no problem with ignoring their freedom of religion.

The winter months proved particularly trying for Mothers with young children. Children had to be bundled up and taken everywhere. Since the latrine, laundry and mess hall facilities were located in separate buildings, often several hundred yards away, a mother would dress and undress her children many times in a day for short trips to eat and do laundry. A child could not be left behind in the barracks for even a moment because of the fire danger that existed. The wooden tar papered barracks with their hot coal burning stoves could ignite and burn to the ground in a matter of minutes.

Second Lieutenant Moe Yonemura of Company C, 442nd Combat Division at Camp Shelby, Mississippi, Photographer: Hikaru Iwasaki, March 20, 1944 (Ethel Ryan Collection #82.01.12.P)

During the spring of 1943, keeping the idea of self-sufficiency in mind, camp administrators proceeded with the development of an agricultural program. The relocation center was located on 42,000 acres of ground belonging to the Bureau of Reclamation. However, before any of the land could be farmed, the canal carrying irrigation water had to be completed. Internee laborers constructed 5,000 feet of canal and used nearly 850 tons of bentonite to waterproof additional sections that had been leaking. Work was completed in the spring of 1943. Several thousand acres of land were cleared of sagebrush and planted in peas, beans, cabbage, carrots, cantaloupe, watermelon, and other fruits and vegetables.

In spite of the belief by local farmers that the canal could not be completed and that crops were planted too late in the year, the autumn harvest yielded 1,065 tons of produce which helped feed the camp's population. An additional 2,500 tons was harvested the following year.

Though milk for Heart Mountain was supplied through contracts with the creamery in Powell, the camp's agricultural program helped supplement meat and egg supplies by raising cattle, hogs and chickens. In fact, egg production at Heart Mountain was so prolific that some internees, after leaving camp, never cared if they ate another egg the rest of their lives.

As the internees were striving to establish a normal life for themselves at Heart Mountain, they could not forget the fact that the world was at war. Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, a number of Japanese Americans were discharged from various branches of the military. Other Japanese Americans who were not serving in the armed forces were designated 4-F, physically or mentally unfit for service, by the United States government. That designation soon changed to 4-C, enemy aliens ineligible for service, even though the young men and women were American citizens. By 1943, with America fighting a war on two fronts, the War Department was in need of soldiers. Japanese Americans were then designated 1-A and told that they were eligible to volunteer for service in a segregated, all-Japanese unit which would serve in Europe. After being forced from their homes on the West Coast and being told initially that they were ineligible for service, only a handful of volunteers from Heart Mountain came forward.

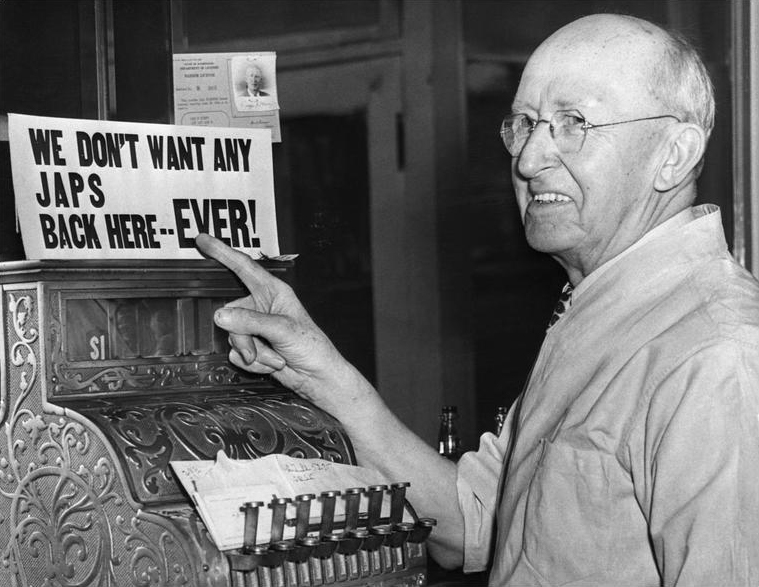

Anti-Japanese sentiments continue after war (WRA #9066P98)

By 1944 the all Nisei 442nd Regimental Combat Team had suffered heavy casualties and was in need of replacements (at that time the 442nd was made up largely of volunteers from Hawaii who had not been interned). In an effort to increase the number of volunteers, the army brought Ben Kuroki, a Nisei war hero, to a number of the relocation centers, including Heart Mountain. Kuroki's speeches about patriotic obligations to America did not impress many of the young men in the camps. Kuroki was a Nebraska farm boy; neither he nor his parents had spent a single day behind the barbed wire confines of a relocation center.

With few volunteers coming forward, the War Department decided to draft men right out of the camps. In response to this move, some Heart Mountain internees established the Fair Play Committee. This committee asserted that internees had no obligation to serve a country that had taken away their freedom. Nearly 100 Heart Mountain draftees refused to serve until their freedom and constitutional rights were restored. The first trial of the Heart Mountain draft resisters was the largest mass trial in Wyoming's history. The resisters were found guilty of refusing to serve and were sent to federal penitentiaries in Kansas and Washington.

Representing the other end of the spectrum, more than 900 men and women from Heart Mountain did serve in both the Pacific and European theaters. Though some were drafted or volunteered after leaving the camp, 654 went directly from Heart Mountain into the service. Twenty were killed in action. Heart Mountain soldiers contributed to the almost mythic legend of the 442nd, which became the most decorated unit in the history of the United States Army.

A central concept of the relocation center was that the inmates could leave the camp, if they located themselves and their families in areas outside the designated military zones on the West Coast. College students were also allowed to leave the center to attend school, if they could find an institution of higher learning willing to accept them. It was easier for a college student to leave camp than a working person with a family. An individual wishing to relocate first had to prove to WRA authorities that he or she had a job waiting on the outside. That individual then filled out a mountain of paperwork, which had to be approved by the WRA. The bureaucratic problems and the uncertain reception waiting on the outside resulted in the majority of the internees remaining in the camps until they closed. In addition, the older Issei who had lost their life?s work, showed little interest in starting life over again at an advanced age.

As internees tried to develop a normal life for themselves at Heart Mountain, problems continued for them on the outside. The city councils of Powell and Cody wanted to stop issuing visitor passes for internees to those communities. During December 1942, Guy Robertson replaced C. E. Rachford as director at Heart Mountain, and in the summer of 1943 he announced that he would not be responsible for upsetting the residents of Powell and Cody. However, when harvest time arrived and Robertson refused to let laborers leave the camp, Ora Bever, the mayor of Powell who had been behind the exclusion efforts of both communities, changed his mind.

Bever informed Guy Robertson that he only meant that the internees could not come to town. He felt that it was all right for them to leave camp and work in the fields. Robertson informed Bever that leaving the camp was leaving the camp. Bever and the Powell council modified their exclusion order while Cody dropped the issue altogether.

Once the crops were in and the area farmers placated, Bever once again moved to exclude the internees from town. He wrote to Governor Lester Hunt stating that the people of Powell were unanimously opposed to the Japanese coming to town. A flood of letters from Powell merchants led Hunt to believe otherwise. A subsequent investigation carried out by the governor's office found that ninety percent of Powell's merchants and more than two-thirds of that community's citizens were not opposed to the issuing of visitor passes to Heart Mountain internees. One Powell resident told an investigator, "I don't like the Japanese, but they are American citizens and should be allowed to go wherever they want." (9)

In spite of problems from outside and from within, the internees did as best they could. Two Japanese words helped them to carry on: "shikata-nai," meaning that things happen which are beyond one's control, and "gaman," which means to persevere in the face of hardship. And the internees did persevere. In December of 1944, one day before the United States Supreme Court handed down a decision in Ex Parte Endo stating that it was illegal for the government to hold loyal American citizens in concentration camps against their will, President Franklin Roosevelt said that the war emergency had ended and internees could return to the West Coast beginning in January of 1945.

On the face of it, Roosevelt's decision seemed to be good news. The majority of the internees at Heart Mountain and other camps, however, no longer had a home on the West Coast. In spite of this fact, the WRA moved forward with plans to close all relocation centers by the end of November 1945. Though the WRA encouraged internees to leave the camp beginning in January of 1945, by June of that year only 2,000 people had left Heart Mountain and its population was still nearly 7,000. Relocation back to the West Coast consisted of giving an internee $25 and a train ticket to the destination of his or her choice. Internees who did not supply administration officials with a home address were simply sent to the area where they resided prior to the war, whether they had a home there or not.

The first internees arrived at Heart Mountain on August 11, 1942. The last trainload of people left Vocation siding below the camp at 8:00 on the evening of November 10, 1945. During the more than three years that the Heart Mountain Relocation Center was open, it saw the birth of 552 babies and the death of 185 internees. The center was of great economic benefit to the state of Wyoming and more particularly to the communities of Powell and Cody. When the camp closed, the Powell Tribune reported that, "The Japanese were well treated here and the whole circumstance of their relocation passes off with few disturbing memories." (10)

Former internees returning to California faced the problems of beginning life again. Many of those with no place to go ended up in WRA-run trailer parks where small camp trailers were rented for $15 per month. At Heart Mountain, the surplus equipment in the camp was auctioned off at fire-sale prices. Former servicemen and hopeful farmers moved in to homestead the land of the Heart Mountain Reclamation Project. Many of those farmers benefited from the construction and waterproofing of the canal, as well as the clearing of land in the area that had been carried out by the internees.

During the years following the end of World War II, Japanese Americans re-established normal lives. There was little talk of the relocation experience amongst those who lived through it. It was an experience which most former internees hoped to forget. However, the 1960s and early 1970s were witness to the Civil Rights movement, and a number of "Sansei" (third generation Japanese Americans) began a movement for redress in an effort to force the United States government to admit to the injustices it had inflicted upon their parents and grandparents.

In 1976, much to the dismay of many Congressmen and Senators, President Gerald Ford repealed Executive Order 9066. Four years later, President Jimmy Carter assisted Japanese Americans with the issue of redress and the Commission on the Wartime Relocation of and Internment of Civilians was created. In 1983, that Commission issued a report titled, Personal Justice Denied, in which it stated that relocation could not be justified under the guise of military necessity. It further found that relocation was the result of war hysteria, race prejudice and a failure of political leadership. In 1990 the federal government issued a check for $20,000 and a signed apology from President George Bush to all surviving former internees. The final phase of redress was the establishment of the Civil Liberties Public Education Fund.

Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, Personal Justice Denied (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1982).

Daniels, Roger, Asian America: Chinese and Japanese in the UnitedStates Since 1850 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1988).

-------, The Politics of Prejudice: The Anti-Japanese Movement inCalifornia and the Struggle for Japanese Exclusion (Berkeley: Universityof California Press, 1962, 2d ed., 1972).

-------, Prisoners Without Trial: Japanese Americans in World WarII (New York: Hill and Wang, 1993).

-------, Sandra C. Taylor and Harry H. L. Kitano, eds., JapaneseAmericans: From Relocation to Redress (Salt Lake City: University ofUtah Press, 1986, revised ed., Seattle: University of Washington Press,1991).

Drinnon, Richard, Keeper of Concentration Camps: Dillon S. Myer andAmerican Racism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987).

Hosokawa, Bill, Nisei: The Quiet Americans (New York: WilliamMorrow, 1969, reprinted, Niwot: University Press of Colorado).

Ichioka, Yuji, The Issei: The World of the First Generation JapaneseImmigrants 1885-1924 (New York: The Free Press, 1988).

Irons, Peter, Justice at War: The Story of the Japanese AmericanInternment Cases (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983).

Kikuchi, Charles, The Kikuchi Diary: Chronicle of an American ConcentrationCamp (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1993).

Okihiro, Gary Y., Cane Fires: The Anti-Japanese Movement in Hawaii(Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1991).

Takaki, Ronald, Strangers from a Different Shore: A History of AsianAmericans (Boston: Little Brown, 1989).

Takezawa, Yasuko I., Breaking the Silence: Redress and Japanese AmericanEthnicity (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1995).

Taylor, Sandra C., Jewel of the Desert: Japanese American Internmentat Topaz (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993).

Weglyn, Michi, Years of Infamy: The Untold Story of America's ConcentrationCamps (New York: William Morrow, 1976).